For Andy Haldane, the Bank of England’s chief economist, recent market ructions and concerns about the health of the Chinese economy could be the beginning of the latest chapter in a three-part “crisis trilogy”.

As China’s three-decade growth miracle comes to an end, the “Anglo-Saxon” crisis of 2008, which was followed by the eurozone’s meltdown in 2011, now threatens to metastasise in emerging markets.

But while it’s clear that China’s double-digit growth rates have come to an end, how low can growth go? And who will be the biggest losers from the end of the commodity boom?

Parallels with yesteryear

While it’s been almost 50 years since the IMF held an annual meeting in South America, some things don’t change.

In 1967, when members convened in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, the fund was led by Pierre-Paul Schweitzer, a French lawyer who took the helm at a time of expansion and creation of the special drawing rights (SDR) club of elite currencies.

“The new world is lower commodity prices which are going to stay low for the foreseeable future"

Mauricio Cárdenas, Colombian finance minister

Christine Lagarde, also a French lawyer, leads the fund at another critical juncture, where quota reform is badly needed and the IMF’s advice – on Greece for example – has not always been heeded.

Pessimists point out parallels between today’s ructions and the Asian crisis of the 1990s. A stronger dollar has sucked money out of emerging economies and back into the rich world, pushing down the value of emerging market currencies.

Optimists say flexible exchange rates have helped to cushion the impact of the downturn, not hinder it, while stockpiles of foreign reserves also provide ammunition to fight off a full-blown crisis.

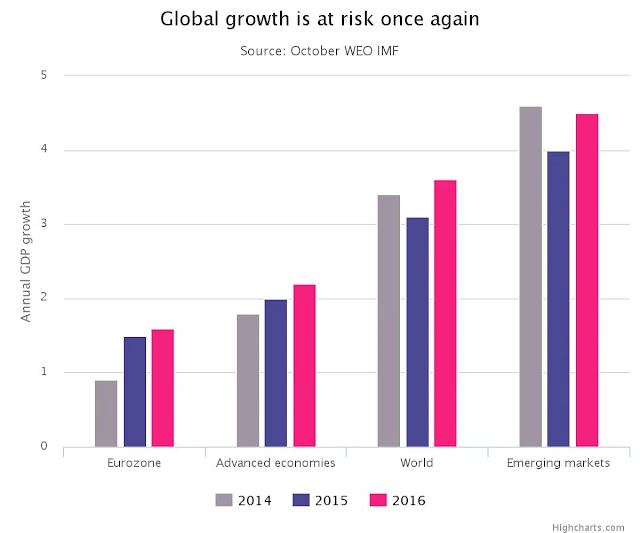

Those who insist the glass is half full also highlight that past crises had a relatively small impact on advanced economies. But pessimists point out that emerging markets now make up the lion’s share of global growth, driving 80pc of world output since 2010, and a much larger slice of global trade.

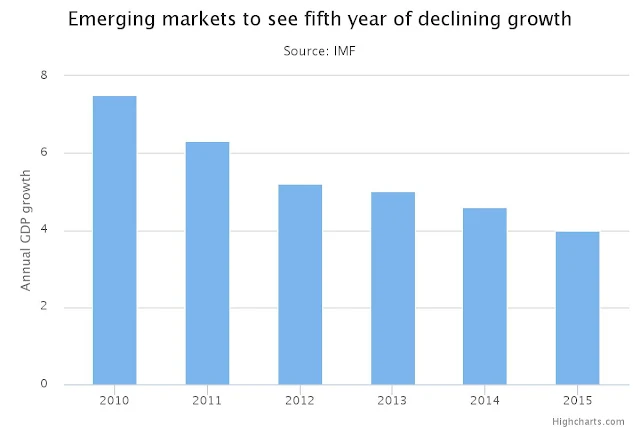

But one thing that everyone accepts is that lower growth is on the way.

Jose Uribe, Colombia’s central bank governor, says it is time to face facts: “We cannot keep trying to grow at the rates of the past.”

Mauricio Cárdenas, the country’s finance minister, describes the situation facing Latin America and other emerging market economies as a simple one: accept reality or deny it.

“We’re in a new world,” he says. “The new world is lower commodity prices which are going to stay low for the foreseeable future. At the same time there is going to be less global liquidity. The US is going to start raising rates in the near future so we’re not making any expectations that we will go back to where we were five or six years ago.”

Colombia has taken difficult decisions as its oil revenues have dwindled.

The country announced $2.4bn (£1.6bn) of budget cuts earlier this year and has warned of more belt tightening in the coming months. Colombia’s central bank raised interest rates in September in a signal that it takes its 2pc to 4pc inflation target seriously, despite flagging growth.

For Cardenas, credibility has been hard won, and he believes keeping Colombia’s house in order will pay off in the long run.

“We thought in advance about this situation. We thought: as oil prices have been falling, we will be investing more in infrastructure so this expansion is offsetting from an aggregate demand point of view the decline in oil rates,” he says.

Cardenas remains confident that Colombia can still flourish without relying on others.

“Whether we succeed is going to be less about the tailwinds from China and from global liquidity from QE, it’s more about us. Previously all countries were surfing on the same wave at the same pace. Now it’s about who is the better swimmer, who has less weight, who has a better sense of direction. Those abilities are going to reflect differences from country to country.”

If Colombia shows how an economy can weather a storm, then the current situation in Brazil serves as a cautionary tale for those who choose profligacy over prudence.

The IMF expects the economy to contract by 3pc this year, and 1pc in 2016 as the economy buckles under the strain of falling commodity prices, high inflation and unemployment.

Its economic troubles have been compounded by political turmoil. A corruption scandal involving state-run energy firm Petrobras has led to a call for the impeachment of president Dilma Rousseff and left her popularity in tatters.

Amid all this, the unpopular government is trying to introduce measures to balance the books.

For Ilan Goldfein, chief economist at Itau, Brazil’s largest private bank, and a former deputy governor of the country’s central bank, sorting out the budget deficit will be crucial to bring investment back into the country.

“You have to adapt to the new reality, and the new reality is that terms of trade are different. Commodities are very different. You can either accept or deny this. If you accept it then you have to tailor your budget to different prices. Oil in Colombia, copper in Chile, iron ore in Brazil: all the commodity producers just have to realise it’s a different business now.

But what lies in store for the countries that do not adjust?

“They will end up like Brazil,” says Goldfein. “Brazil basically denied the reality for four years. The diagnosis was: something is happening, the government is not stimulating enough, we are not spending enough, there is not enough credit, there are not enough public subsidies so we should just push, push, push.

“But in the same way Brazil benefited from the boom, it now has to deal with the bust.”

Holy Grail of global growth

The dilemma now facing emerging markets has posed a bigger question: where is growth going to come from now that the emerging market engine is stalling?

Maurice Obstfeld, the IMF’s new chief economist, said last week that the “holy grail” of robust global growth remained “elusive” – six years on from the Great Recession.

Central banks around the world have cut interest rates more than 600 times since Lehman Brothers collapsed, yet this has not been enough to secure the recovery.

Obstfeld’s predecessor, Olivier Blanchard, who retired from the post at the end of last month, is more upbeat than the tone of the latest IMF health checks suggest.

Blanchard is used to hearing the Financial Stability Report forecasting the end of the world every six months.

“At this stage, I’m not very worried. Sure, the baseline is unexciting. Sure, there are risks, coming from the real economy or the financial sector. The nature of the risks keeps changing. But I don’t think at this stage the risks are larger than they have been in the recent past,” he says.

Blanchard is particularly calm about China, and says claims that economic growth could be slowing to an annual pace of between 2pc and 3pc are not based in fact. He says the IMF spent a lot of time talking to Chinese policymakers over the summer.

Consumer spending remains strong, he says, while housing investment, which has already fallen sharply, is no longer in danger of collapse. The problem is state investment he says, and while preventing Schumpeter’s gale from blowing unproductive companies down is not ideal, he believes the state could ensure that a hard landing stemming from this sector is avoided.

“Over time, China growth will slow down, but the probability that it will suddenly collapse to 3pc to 4pc or less is small,” he says.

Blanchard is now looking for ways to avoid what Lagarde has described as a “new mediocre”. One way to ensure monetary policy remains potent in times of low growth would be to set a higher inflation target, says Blanchard, in an idea he put forward a few years ago.

A higher inflation target implies that rates can fall further, making it more likely that policymakers can support employment and fight off recessions.

However, the Bank of England's Haldane says this policy would probably prove unpopular with the public. People – in Britain at least – already believe prices are rising faster than official data show.

“When the public are asked directly about the inflation target, they suggest, on average, that it may if anything be a little too high,” he said recently.

The Bank’s latest inflation attitudes survey shows the public thought prices rose by 2.1pc in the year to August, when inflation was in fact zero.

The survey also showed more than half of people believe the Bank’s current target of 2pc inflation was “about right”. Just 7pc said it was too low, while 45pc said a higher inflation target would “make the economy weaker”.

Negative interest rates are an alternative to a higher inflation target, but again this has its pitfalls. Negative deposit rates at banks could end up slowing the economy unless policymakers banned cash so customers couldn’t withdraw their savings and hoard them under the mattress. This seems like a long way off. It’s unlikely we will be buying bananas with bitcoin just yet.

But the challenge facing policymakers is serious. “If a really bad shock happened – and I have no clue as to what form it would take – the room for fiscal or monetary policy response would be limited,” says Blanchard.

Goldfein believes many emerging market economies will also join in the quest for higher growth.

“I think this debate on low productivity and growth will spread from the US and other advanced economies all over the globe. Countries won’t boom any more, they’ll just grow.

“People will think 1pc, 1.5pc growth… I need much more than that to become rich as an emerging market. We’ll be having these conversations over the next five years.”

For now Lima’s clouds continue to obscure the horizon, as uncertainty about China’s slowdown clouds the outlook. The sun’s not ready to come out. Not yet, anyway.

Comments

Post a Comment